4 December 2022

Tor field-station consists of two containers put side by side. One of them is a small workshop and laboratory and another serves as a living cabin. There are bunk beds, dining table, small heater, kitchenette, shelves, and two windows with great views. Next to it there are also small hut and igloo-building which are used for storage. They are older and were constructed about 30 years ago, when scientists started their work here. We also have barrels for gray water and other disposals, which we will bring back to Troll. All rubbish and waste have to be taken out of Antarctica. We do not need a fridge. We keep our frozen food outside, because it is usually below -15 degrees Celsius outside.

Living in a remote field station, we develop some routines. We normally wake up at 5:00 in the morning, and then after a quick breakfast, we check our instruments, tools and go to work in the field from around 6:30. Svarthamaren is a specially protected area in Antarctica and to work here we need a special permit. It is a sanctuary for three species of Antarctic birds: Antarctic petrel, snow petrel and skua. They all come here to breed during the summer season. Snow petrels are the smallest of the birds, they weight about 300 grams, are distinctively white, and nest under rocks. In fact, every cavity between the rocks is a potential nest. Antarctic petrels are bigger, they have black heads and ends of their wings, and nest on rocky slopes. Skuas are the biggest, brown birds in the colony. They remind me of eagles, especially when they present their wings when marking their territory. They nest in the open areas, usually at the bottom of the mountain. There are many thousands of petrels nesting here and the whole mountain is vivid and loud. There are much fewer skuas. These are the largest predator birds in Antarctica. Skuas soar above the petrel nests and between other birds, and they search for abandoned eggs or weaker petrels.

The whole mountain is a cycle of life in its purest form. We see parents carefully guarding their eggs and taking care of each other. They shift each other on the eggs: one is incubating for about a week, while the other is feeding at sea. A new life will be born six weeks after the egg is laid. At the same time, there are many birds which will not make it through the seasons. Their corpses, yellowish and mummified in the cold, cover the ground. Some of them are certainly thousands of years old, as the bird colony has certainly been here for thousands of years! In the beginning, walking through deposits of bird bones and wings, and seeing lively birds sitting in nests with dead chicks was shocking to me, but then I had to accept that it is simply a circle of life in a magnifying glass. Antarctica is harsh and cold, and what matters to these birds is to survive and give new life. But not all of them will see the sea again.

Sebastien Descamps is a biologist at the Norwegian Polar Institute. He has been coming to Svarthamaren for the last ten years to study birds in this unique place. He had to cancel the last year expedition because there was surprisingly no bird at the mountain, while in the previous years there were tens of thousands breeding pairs. Last year, the long-lasting storm prevented birds to breed and forced them to return to the sea. I ask him what are the consequences for these species? He replies that seabirds live long, and hopefully the impacts will be limited. However, there is also an alarming longer trend of decreasing population, and we do not know if it is only a regional or global trend.

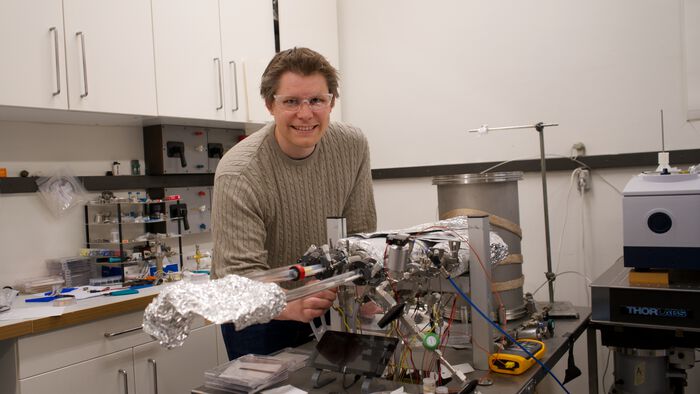

I am joining Sebastien in the fieldwork. We are partners in the TONe infrastructure project, which stands for Troll Observing Network, and each of us is responsible for a work package in the project. While my expertise is in physics and his in biology, we join forces to carry out joint fieldworks. I am running instruments for space weather monitoring here at Tor, and whenever I can, I join Sebastien in monitoring the bird population. In Antarctica, we need to collaborate across disciplines.

This joint fieldwork follows the spirit of the TONe project, in which many Norwegian institutions collaborate to further develop observation network in Dronning Maud Land. As a part of TONe, we deploy several automatic cameras in the colonies of Antarctic petrels and snow petrels. They will collect data during the whole season for studying the dynamics of changes in the colony. I am joking that from a distance the camera enclosures look like helmets of soldiers from the Star Wars movie that now guard the colony.

We also monitor bird nests in selected areas, deploy loggers to track bird movements and migration, check their weight, take blood samples, and collect oil to study their diet. Yes, oil! Petrels spit oil, which smells of fish. This is their food which they store for chicks and for themselves. But they also spit this oil on other birds during disagreements. Very often, we see snow petrels that are not white, but orange! They land on snow to clean themselves, and they can take this snow bath for hours. Oily feathers mean worse insulation and loosing heat more rapidly, and they do not want it here. Petrels sometimes also spit on us when we get too close too fast. Our jackets then smell like oil from mackerel in tomato sauce.

In the evenings, the winds from the Antarctic plateau pick up and the birds soar high above the slopes of Svarthamaren until late morning hours. This is a magnificent sight. When they get to high altitudes, they can easily reach the ocean and feed themselves. They need to glide for about 200 kilometers. It is aerodynamics at work! Flying at different levels they form a very dynamic three-dimensional picture. We feel surrounded by birds in the middle of this wonder. Sometimes, I recall that the closest civilization and other people are kilometers away at Troll. Here at Tor, we are only two scientists and many thousands of birds. We are like on a small island surrounded by the ocean of ice.

Sebastien is quite optimistic when it comes to the birds at Svarthamaren this season. The fact that they returned here and that most of them have already eggs are already good signs. How many birds are here, we will see in a few days., when we will go through the whole colony and count birds in selected areas to estimate their density. We will leave in about one week, and the birds will stay here monitored throughout the season by many cameras.

Wojciech J. Miloch

Department of Physics

University of Oslo

Plasma and space physicist Wojciech Miloch is on a month-long mission to Antarctica, to the Norwegian research stations Troll and Tor to set up and test new instruments. He is traveling with a bird researching colleague. Through a slow satellite phone line we receive reports from the field.